David Kraemer applied math phd student

When abstraction is simpler

I am always delighted when abstraction makes a problem noticeably easier to solve. Today I encountered (Jacod 1999) the following homework question:

Let \(Y \sim N(0,1)\) be standard-normally disributed, and let \(a > 0\). Let

\[\newcommand{\abs}[1]{\vert#1\vert} Z = \begin{cases} Y & |Y| \leq a, \\ -Y & |Y| > a. \end{cases}\]Show that \(Z \sim N(0,1)\) as well.

I honestly groaned when I first read it, because I imagined that I might have to evaluate some integrals involving a Gaussian kernel and error functions. This is not my favorite activity.

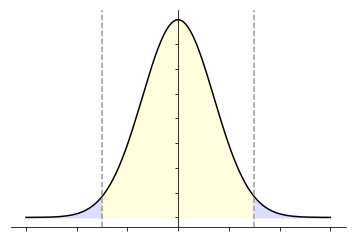

As I thought through it, I realized that I had no basic intuition for how to proceed with the solution, so I did what I love do: draw a picture. I ended up with something that resembled the following picture.1

Here the yellowish region indicates when \(\abs{Y} \leq a\) and the bluish regions indicate when \(\abs{Y} > a\).

As I started playing around with the plot, I realized that if \(|Y| \leq a\) then this simply meant that \(Z\) would behave exactly as \(Y\), but if \(|Y| > a\) then the behavior would “flip” around the origin. But was the “flip” consequential? Apparently not, because the extremes are shaped symmetrically.

Actually the whole plot is symmetric, and this is well known about Gaussian kernels. My intuition had nothing to do with density functions that specifically followed \(\exp(-x^2)\), however. I really was just interested that \(|Y|\) was symmetrically distributed.

So I started thinking about symmetrically distributed random variables as an abstraction over this particular instance. It turns out that the proof falls out easily if you just take this assumption:

Proof. If \(Y\) is symmetrically distributed, then \(Y\) and \(-Y\) are identically distributed, and

\[P(Y \leq y) = P(-Y \leq y).\]To determine \(P(Z \leq z)\), condition on \(\abs{Y}\). In particular, we can write

\[P(Z \leq z) = P(Y \leq z) P(|Y| \leq a) + P(-Y \leq z) P(|Y| > a).\]But since \(Y\) is symmetrically distributed, this implies

\[P(Z \leq z) = P(Y \leq z) [P(|Y| \leq a) + P(|Y| > a)],\]and as \(P(|Y| \leq a) + P(|Y| > a) = 1\), we conclude that \(P(Z \leq z) = P(Y \leq z)\), which means that \(Z\) and \(Y\) are identically distributed. \(\square\)

There are substantial reasons to prefer this result over the statement of the homework problem. For one, this fact doesn’t even require that \(Y\) have a density function. It applies to any symmetric distribution, whether discrete, continuous, singular, or mixed.

Truthfully, I enjoy these sorts of arguments not particularly because of the generality, but because they’re so simple. When I thought in terms of Gaussians and error functions, I was sweating the details of nasty integrals and proper bounds. The general case, by abstracting over those details, directs you to “cut to the chase.” Which assumptions are absolutely essential? Okay, well I’ll have to use those somewhere. The rest I can discard. In this sense, by abstracting, I “restricted” my toolkit and identified the important devices.

Of course this strategy doesn’t always work. Sometimes many properties, specific and general, are required to make an argument go through. Needless generality can easily obfuscate what’s actually going on, too, and this ruins rather than refines intuition.

This sort of exercise represents a “sweet spot” of abstraction. The payoff is a direct, clear argument, but one that remains connected to the original problem.

Published on April 4th, 2018 by David Kraemer